click to enlarge.

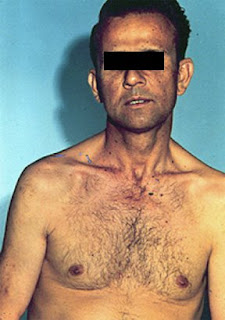

a friend of mine had his exam recently.

he had a tall patient in station 5 and was asked to come with a diagnosis.

he was confused between Marfan's and Klinefelter's syndromes!

how would you differentiate?

Dear friends and colleagues, Passing the MRCP UK is an important step in the medical career. PACES is the practical clinical exam and require a wide breadth of knowledge. This blog is a space to share materials, information and knowledge and I hope you find it useful. Am open for any ideas or suggestion and would value your contributions and comments. please visit my related pages on facebook and youtube. Best wishes, Dr Elmuhtady Said

follow these steps in CVS examination:

Introduction : Hello Mr Smith,

My name is Dr X ; I'm a medical SHO,

Can I examine your heart please?

Position : 45 degree

Is it sore anywhere?

Exposure: can you take your shirt please?

General inspection : stand back,

Ask the patient to take deep breath in,

Look is he comfortable at rest, is he SOB?

Look for catheter, peripheral oedema, GTN, OXYGEN,

Malar rash,Lip cyanosis, BP apparatus.

Hands : look for warm/cold

Clubbing

Splinter haemorrhage

Xanthoma

Tobacco staining

![]() Arm: pulse (rate, rhythm, volume, character & synchronous) Radio-radial delay

Arm: pulse (rate, rhythm, volume, character & synchronous) Radio-radial delay

Collapsing pulse (ask for pain in shoulder)

Radio-femoral delay

Brachial pulse & anti cubital fosaa scar.

Feel carotid pulse & comment on character.

Face:

eyes for paller, xanthlasma

Mouth for tongue, cyanosis

Conclude by saying:

I would like to finish ex by

checking signs of heart failure

(auscultating lung bases, looking for hepatomegaly, pedal oedema and sacral oedema).

Checking BP.

Checking urine

Examples from GMC

Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together.

Refusal of treatment:

C had paranoid schizophrenia and was detained in Broadmoor Secure hospital. He developed gangrene in his leg but refused to agree to an amputation, which doctors considered as necessary to save his life .the court uphold C’s decision.

→ the fact that a person has a mental illness does not automatically mean they lack capacity to make decision about medical treatment.

Right of a patient who has capacity to refuse life-prolonging treatment:

B was 43 years old woman who had become tetraplegic and who no longer wished to be kept alive by means of artificial ventilation .she asked for ventilation to be withdrawn but the doctors caring for her were un willing to agree to this.B whose mental capacity was unimpaired by her illness, sought and obtained a declaration from the court that the hospital was acting unlawfully.

→A competent patient has the right to refuse treatment and their refusal must be respected, even if it results in their death.

Right to refuse treatment even if it resulted in harm to unborn child:

S was diagnosed with pre-eclampsia requiring admission to the hospital and induction of labour, but refused treatment because she did not agree with medical intervention in pregnancy. Although competent and not suffering from a serious mental illness, S was detained for assessment under the mental health act .A judge made a declaration overriding the need for her consent to treatment, and the baby was delivered by caesarean section.

The appeal court held that S’s right to autonomy had been violated, her detention had been unlawful (since it has been motivated not by her mental state but by the need to treat her pre-eclampsia) and that the judicial authority for caesarean section had been based on false and incomplete information.

→A competent pregnant woman can refuse treatment even if that refusal may result in harm to her or her unborn baby. Patients can not lawfully be detained and compulsorily treated for a physical condition under the term of the mental health act.

Can you add more example?

Ethics…important definitions

Competence:

The assessment of a patient’s capacity to make a decision about medical treatment is a matter for clinical judgement guided by professional practice and subject to legal requirements.

To demonstrate capacity individuals should be able to:

understand (with the use of communication aids, if appropriate) in simple language what the medical treatment is, its purpose and nature and why it is being proposed;

understand its principal benefits, risks and alternatives;

understand in broad terms what will be the consequences of not receiving the proposed treatment;

retain the information for long enough to use it and weigh it in the balance in order to arrive at a decision

Communicate the decision (by any means).

In order for the consent to be valid the patient must be able to make a free choice (i.e. free from pressure).

Capacity:

You must work on the presumption that every adult patient has the capacity to make decisions about their care, and to decide weather to agree to, or refuse an examination, investigation or treatment.

You must only regard a patient as lacking capacity once it is clear that, having given all appropriate help and support, they can not understand, retain, use or weigh up the information needed to make decision or communicate their wishes.

In England and Wales, the Mental Capacity Act allows people over 18 years of age, who have capacity, to make a Lasting Power of Attorney appointing a welfare attorney to make health and personal welfare decisions on their behalf once capacity is lost.

The Court of Protection may also appoint a deputy to make these decisions.

Neither welfare attorneys nor deputies can demand treatment which is clinically inappropriate.

Where there is no welfare attorney or deputy the doctor may treat a patient who lacks capacity, without consent, providing the treatment is necessary and in the patient’s best interests.

The Act also requires doctors to take into account, so far as is reasonable and practicable, the views of the patient’s primary carer.

In Scotland, the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act allows people over 16 years of age to appoint a welfare attorney who has the power to give consent to medical treatment when the patient loses capacity.

The Court of Session may also appoint a welfare guardian on behalf of an incapacitated adult.

Neither welfare attorneys nor guardians can demand treatment which is judged to be against the patient’s interests.

Where there is no proxy decision maker, doctors have a general authority to treat a patient who is incapable of giving consent to the treatment in question.

The Act also requires doctors to take into account, so far as is reasonable and practicable, into the views of the patient’s nearest relative and his or her primary carer.

In Northern Ireland, no person can give consent to medical treatment on behalf of another adult. As the law currently stands, doctors may treat a patient who lacks capacity, without consent, providing the treatment is necessary and in the patient’s best interests

Best interest:

A number of factors should be addressed when considering what the patient best interest is, including:

The patient’s own wishes and values (where these can be ascertained), including any advance decision;

Clinical judgement about the effectiveness of the proposed treatment, particularly in relation to other options;

Where there is more than one option, which option is least restrictive of the patient’s future choices?

The likelihood and extent of any degree of improvement in the patient’s condition if treatment is provided;

The views of the parents, if the patient is a child;

the views of people close to the patient, especially close relatives, partners, carers, welfare attorneys, court-appointed deputies or guardians about what the patient is likely to see as beneficial; and

Any knowledge of the patient’s religious, cultural and other non-medical views that might have an impact on the patient’s wishes.

Advance decision:

Advance refusals of treatment have long been legally binding under common law. Advance requests or authorisations have not had the same binding status but should be taken into account in assessing best interests.

Following the Burke case in 2005, it is accepted that there is a duty to take reasonable steps to keep the patient alive (e.g. by provision of artificial nutrition and hydration) where that is the patient’s known wish.

In England and Wales, advance decisions are covered by the Mental Capacity Act. Patients who are aged 18 or over who have capacity may make an advance refusal of treatment orally or in writing which will apply if they lose capacity.

To be valid and legally binding the advance decision must be specific about the treatment that is being refused and the circumstances in which the refusal will apply.

Where the patient’s advance decision relates to a refusal of life-prolonging treatment this must be recorded in writing and witnessed.

The patient must acknowledge in the written decision that they intend to refuse treatment even though this puts their life at risk.

In Scotland and Northern Ireland, advance decisions are not covered by statute but it is likely they are covered by common law.

An advance refusal of treatment is likely to be binding in Scotland and Northern Ireland if the patient was an adult at the time the decision was made (16 years old in Scotland and 18 years old in Northern Ireland).

The patient must have had capacity at the time the decision was made and the circumstances that have arisen must be those that were envisaged by the patient.

Confidentiality:

Patients have the right to expect that information about them will be held in confidence by their doctors.

In the legal perspective, it is in the public interest for the patient to be able to trust their doctor to maintain confidentialty.for this reason, this obligation is not absolute.

Information must be disclosed when there is statutory duty. Examples include:

notification of infectious disease

drug addiction

termination of pregnancy

birth and death

identification of a patient undergoing in vitro fertility treatment with donated gametes

identification of donor and recipient for transplanted organ

prevention, apprehension or prosecution of terrorist

police on request, name and address nut not clinical details

under court orders

In one study, physicians did not allow patients to complete their opening statements 69% of the time. The mean time until the first interruption was 18 seconds. Once interrupted, fewer than 2% of patients went on to complete their statements.

"Data are thus very much physician-determined, skewed toward problems that are biomedical in nature... It has been proposed that current interviewing practices are at odds with scientific requirements: They produce biased, incomplete data about the patient."

Goal: To establish a favorable context for the interview

Welcome the patient

Know and use the patient's name

Introduce and identify yourself

Ensure comfort and privacy

Goal: To establish the agenda for the interview

Obtain list of all issues - avoid detail

Chief Complaint

Other complaints or symptoms

Specific requests (i.e. medication refills)

Patient's expectations for this visit

Ask the patient "Why now?"

Goal: To establish a good flow of information

Open-ended questions initially

Encourage with silence, nonverbal cues, and verbal cues

Focus by paraphrasing and summarizing

Goal: To smoothly shift into physician-centered interviewing

Summarize interview up to that point

Verbalize your intention to make the transition

This should be clear from the transition summary.

Move from general to specific

Flow from open-ended to closed-ended questions

Allergies/Adverse Reactions

Medications/Immunizations

Major Medical or Psychiatric Problems/Major Surgeries

Last Menstrual Period/Pregnancies/Contraception (if female)

Smoking/Alcohol/Caffeine/Other Drugs

Family/Social History

Occupational History

Sexual History